The immune system has to be tightly regulated to avoid collateral damage. The discovery of regulatory cells in 1985 yielded one of the most important immunological advances in the past 50 years (Sakaguchi et al. J Exp Med 1985). These regulatory cells, among which CD4+Foxp3+ are the best characterized, were found to suppress the immune response, preventing it from getting out of control. These cells are also responsible for maintaining tolerance to our own tissue, preventing auto-reactive T cells from destroying self-tissue. Humans with mutations in the Foxp3 gene develop a life-threatening polyautoimmunity involving multiple organs (IPEX syndrome), confirming the critical importance of this cell subset in maintaining self-tolerance (Wildin et al. J Med Genet 2002). Furthermore, in the most physiological model of allogeneic tolerance (pregnancy), Tregs and immune regulatory signals have been shown to be critical for maternal tolerance to the fetus (Aluvihare et al. Nat 2004; Kahn et al. PNAS 2010; Riella et al. Am J Path 2013; D’Addio, Riella et al. J Immun 2011). Finally, blocking regulatory pathways such as by using anti-PD1 or anti-CTLA4 in cancer is associated with significant side effects related to auto-immunity.

The immune system has to be tightly regulated to avoid collateral damage. The discovery of regulatory cells in 1985 yielded one of the most important immunological advances in the past 50 years (Sakaguchi et al. J Exp Med 1985). These regulatory cells, among which CD4+Foxp3+ are the best characterized, were found to suppress the immune response, preventing it from getting out of control. These cells are also responsible for maintaining tolerance to our own tissue, preventing auto-reactive T cells from destroying self-tissue. Humans with mutations in the Foxp3 gene develop a life-threatening polyautoimmunity involving multiple organs (IPEX syndrome), confirming the critical importance of this cell subset in maintaining self-tolerance (Wildin et al. J Med Genet 2002). Furthermore, in the most physiological model of allogeneic tolerance (pregnancy), Tregs and immune regulatory signals have been shown to be critical for maternal tolerance to the fetus (Aluvihare et al. Nat 2004; Kahn et al. PNAS 2010; Riella et al. Am J Path 2013; D’Addio, Riella et al. J Immun 2011). Finally, blocking regulatory pathways such as by using anti-PD1 or anti-CTLA4 in cancer is associated with significant side effects related to auto-immunity.

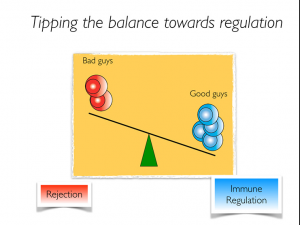

In transplantation, the balance between pathogenic T cells and regulatory T cells determine the fate of the immune response (Fig. 1). Therefore, tipping the balance towards regulation may allow a reduction in the amount of immunosuppression required in the long-term based on the increased immune modulation provided by Tregs, reducing the risk of infection, malignancies and metabolic complications. Preclinical studies have clearly showed the potential of Tregs in preventing acute and chronic allograft rejection (Joffre et al. Nat Imm 2008; Waaga-Gasser et al. JASN 2009). Furthermore, affecting Treg survival signals is capable of precipitating rejection (Riella et al. AJT 2012; Safa et al. JASN 2015). Lastly, expansion of Tregs promoted islet cell acceptance and was also protective in kidney ischemic reperfusion injury in mice (Webster et al. J Ex Med 2009; Kim et al. JASN 2013).

In transplantation, the balance between pathogenic T cells and regulatory T cells determine the fate of the immune response (Fig. 1). Therefore, tipping the balance towards regulation may allow a reduction in the amount of immunosuppression required in the long-term based on the increased immune modulation provided by Tregs, reducing the risk of infection, malignancies and metabolic complications. Preclinical studies have clearly showed the potential of Tregs in preventing acute and chronic allograft rejection (Joffre et al. Nat Imm 2008; Waaga-Gasser et al. JASN 2009). Furthermore, affecting Treg survival signals is capable of precipitating rejection (Riella et al. AJT 2012; Safa et al. JASN 2015). Lastly, expansion of Tregs promoted islet cell acceptance and was also protective in kidney ischemic reperfusion injury in mice (Webster et al. J Ex Med 2009; Kim et al. JASN 2013).

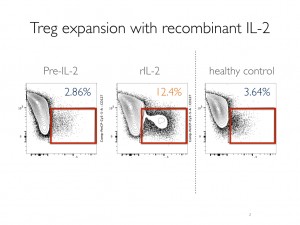

There are different potential strategies to expand Tregs, including manipulating specific costimulatory/coinhibitory pathways, administration of agents that promote Tregs (e.g. low-doseIL-2) or adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded Tregs. Promising results of targeting Tregs in bone marrow transplantation in humans have been shown: expansion of Tregs with low-dose IL-2 in refractory chronic GVHD was capable of controlling disease (Koreth et al. NEJM 2011). In human solid organ transplantation, operationally tolerant kidney and liver recipients have a significant expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs, in particular memory Tregs (Braza et al. JASN 2015; Martinez-Lloredella et al. AJT 2007). In the worse case scenario of not achieving tolerance, one of the greatest advantages of targeting Tregs is that patients will most likely be able to reduce the amount of immunosuppressive medication required in the long-term due to the increased immune modulation provided by those Tregs. It will also be critical to use immunosuppressive drugs more wisely, avoiding the use of drugs with deleterious effects on Tregs. In my lab, we are currently working o n pathways that selectively expand Tregs with exciting data in murine transplant models (Murakami, Riella Transp 2014). In the clinic, I am co-investigator of an ongoing clinical trial in transplantation using low-dose IL-2 to expand Tregs. Though too soon to share results, Tregs were expanded by 4-fold after IL-2 therapy (Fig. 2) without any effect on effector T cells, demonstrating the feasibility of this strategy to expand Tregs in humans. Treg adoptive transfer studies are also underway in transplantation (see blog). In sum, selective inhibition of effector T cells with promotion of Tregs post-transplant is a desirable strategy to improve long-term graft survival. Exciting upcoming trials in humans will determine the efficacy of this strategy in improving graft outcomes.

n pathways that selectively expand Tregs with exciting data in murine transplant models (Murakami, Riella Transp 2014). In the clinic, I am co-investigator of an ongoing clinical trial in transplantation using low-dose IL-2 to expand Tregs. Though too soon to share results, Tregs were expanded by 4-fold after IL-2 therapy (Fig. 2) without any effect on effector T cells, demonstrating the feasibility of this strategy to expand Tregs in humans. Treg adoptive transfer studies are also underway in transplantation (see blog). In sum, selective inhibition of effector T cells with promotion of Tregs post-transplant is a desirable strategy to improve long-term graft survival. Exciting upcoming trials in humans will determine the efficacy of this strategy in improving graft outcomes.